Take Five: Not knowing who you are until you find out

Many discoveries old and new this week, with plenty for the reading set: Seymour Krim, Arthur magazine, and the script for 'Two-Lane Blacktop,' plus some music from Tina Brooks and the Beach Boys

“Take Five” is posted each Friday, and offers five things I spent some time with over the course of the previous week. No criticism, no in-depth analysis, just a few things I think you might be interested in checking out. When the spirit moves me, I’ll post other things at other times.

After several music-heavy offerings here over the past few weeks, here is one for the readers in our midst. There is still music, of course, but if you're looking for interesting things to read, um, read on.

1. Seymour Krim — 'For My Brothers and Sisters in the Failure Business'

Part of my day job involves celebrating literary Iowa City, so I'm always on the lookout for authors with local ties. I'm not sure where I came across Seymour Krim, but I jotted down the name a few months ago and finally looked him up this week. Krim was a critic, chronicler of the Beats, proponent of "New Journalism," essayist, and teacher. That last role brought him to the Iowa Writers' Workshop in the 1970s, where he steered the likes of Tracy Kidder toward nonfiction (with, one must admit, stunning results). He seems to have largely faded from view, but I was able to track down a well-known essay of his, "For My Brothers and Sisters in the Failure Business," anthologized in Phillip Lopate's 1994 collection, The Art of the Personal Essay. Writing at age 51 — younger than I am now — he is clear-eyed about the eternal elusiveness American Dream, seemingly more content than resigned. Though written in 1973, it seems to speak to the malaise that fuels much of today's fractured politics. He writes of "the thousands upon thousands of people who I believe are like me… who have never found the professional skin to fit the riot in their souls." The passage that stopped me in my tracks seems to describe the half of our country with a perennial chip on its shoulder:

The handy magic of relying on the future, on tomorrow, to knit together all the parts of a self that we hoarded up for a lifetime can't be stopped at this late date, or won't be stopped, because our frame of mind was always that of a long-odds gambler. One day it would all pay off. But for most of us, I'm afraid that day will never come."

So many spend a lifetime creating a self, and then grow bitter when that shell doesn’t lead anywhere.

I look forward to tracking down more of Krim’s work and trying to figure out more about his ties to the University.

(I can’t footnote the headline of this piece, so I’ll just offer that it’s another quote from this Krim essay that is yet another apt description of America, which he describes as the “they-broke-the-mold incubator of not knowing who you are until you find out.” Is there a more down-to-earth summation of our supposed egalitarian homeland… or this weekly catch-all in my endless quest to brighten the corners1 of my cultural world?)

2. Tina Brooks — True Blue

I'm not sure when I first heard of Tina Brooks, but when I first heard him was during the early days of Napster. I downloaded most of his debut — and the only album released during his lifetime — True Blue, and fell for its classic hard bop sound. I've since made up for that bit of theft, picking up the Rudy Van Gelder edition on CD in 2005 and, in what is an increasingly common practice, now on vinyl. I had the chance to spin it earlier this week, and it leaped from the speakers. It features a front line of Brooks' tenor sax and 22-year-old trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, recorded just six days after the two fronted the band for Hubbard's Blue Note debut, Open Sesame. Brooks led four sessions for Blue Note between 1958 and 1961. The other three were all released posthumously, and all are worth hearing, but for me, True Blue is the best. The North Carolina-born Brooks cut his teeth in R'n'B bands, and there is a strong sense of melody carried over to his jazz work. All five tracks here are Brooks originals (he also wrote two of the six tracks on the Hubbard album), and all shine with Brooks' and Hubbard's bright, clear solos. Yes, as you listen to “Good Old Soul,” you know these are musicians who have heard “Moanin’,” and there is nothing wrong with that. Brooks stopped recording in 1961, when he was just 28, plagued by drug addiction and poor health, dying in 1974 with this one record to his name. We’re lucky to have all four, and if you like what you hear above, I highly recommend them all.

3. Arthur magazine returns… sort of

During its lifetime, I only ever got my hands on one print issue of Arthur magazine. Started in 2002 by Jay Babcock2, it was a smart California-based periodical that covered the counterculture in a way that Rolling Stone did in its earliest days. I sought it out for the music coverage, but it also dealt with movies, books, visual art, and other cultural affairs. Now, I can catch up, and so can you, thanks to Babcock's efforts to digitize 19 issues and counting of the 35 that were published. Download a PDF and immerse yourself in the left-of-center world of the aughts (the magazine ran from 2002-08, and then again for a short resurrection in 2012-13). I took a look at issue 15 from March 2005, intrigued by the cover interview with Ben Chasny from the band Six Organs of Admittance. This was from around the time of the first album from the band that caught my attention, School of the Flower, and it is interesting to see where Chasny's thinking about his music was at two decades ago. "That is something to aspire to," he said, "to find the dirt in a melody and a flower in the chaos." But I also read everything from an interview with power popper (and erstwhile Raconteur) Brendan Benson about his tea habit to a piece about a film featuring the work of outsider artist Henry Darger. I guarantee you’ll discover something you didn’t know before, or at least learn more about something you thought you already knew.

4. Rudy Wurlitzer and Will Corry — 'Two-Lane Blacktop' script

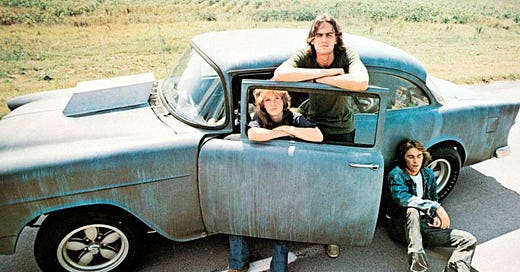

These last two items are thanks to the Jokermen podcast, which started life as two young guys listening to and responding to Bob Dylan albums (hence the Infidels-referencing name), and has evolved to cover other artists including new focus the Beach Boys. The two hosts venture beyond the albums when exploring a discography, and a recent episode discussing drummer Dennis Wilson's film debut, “Two-Lane Blacktop,” sent me to the box in the basement filled with VHS tapes to pull out my copy. I hadn't watched this 1970s film by Monte Hellman in years, but it has aged surprisingly well. This story of two young men who race a '55 Chevy at stops across the county — the Mechanic (Wilson) and the Driver (James Taylor… yes, that James Taylor) — is a minimalist travelogue. I had heard that the screenplay was longer and more detailed, and I finally tracked it down in a 1971 issue of Esquire magazine, back when men's magazines did that sort of thing. I read it this week, and it explains why Hellman's first cut of the movie was more than three hours long. In the 100-minute cut that was released, the already spare dialogue is trimmed significantly, with much exposition left on the cutting room floor. The screenplay is by Rudolph Wurlitzer and Will Corry. I've read a couple of Wurlitzer's '70s novels and was interested to see how this compares. I can't imagine reading it without having seen the film first, but it is a compelling script that explicates and enhances the film. An early line pretty well sums up what you'll see:

"The Mechanic never talks when he's working, as the Driver never talks when he's driving."

The disaffected, aimless stance of the three young people in the film — the Driver and the Mechanic are joined by the Girl — stand in contrast to the anxious questing of the fourth character, the thirtysomething GTO (yes, he drives a GTO, and is played by the always interesting Warren Oates).

Girl: Say, which way are we going?

Mechanic: East.

Girl: That's cool. I never been east.

Meanwhile, in a role reversal, they are almost oddly parental to the older driver racing them across the country.

Girl: This is not really like a race. I mean, first we follow him and then he follows us.

Mechanic: He needs encouragement or he's likely to fade.

If you’ve seen the film, it’s worth tracking down the screenplay to flesh out the spare tale.

Beach Boys — “’Til I Die’

The second Beach Boys-related item is a little path I followed thanks to a Jokermen episode on the Boys' 19713 album, Surf's Up. Joined by Alexis Taylor from the British band, Hot Chip, they discuss this odd album that features beautiful Carl Wilson tunes like "Feel Flows" and "Long Promised Road," embarrassing Mike Love tracks like "Student Demonstration Time," Smile excavations like the title track, and new masterpieces like “'Til I Die.”4 It was the last of these that captivated me this week. Taylor mentioned a mix of the song created by engineer Stephen Desper found on the soundtrack to a documentary about the band that brings each of the instruments and other elements into the song one at a time. Because so much of the Boys' appeal is in their vocal harmonies, there are plenty of mixes and compilations that feature a capella versions of their songs, but this one shows how Brian Wilson built a song —with instruments and vocals — into a work of art. It starts with the bass, then adds vibes, then keyboard, then drums and so on, before adding the stacked vocals that are Wilson’s trademark. The separation shows how each element complements the others. It is one of Brian Wilson's most enduring melodies, and hearing it in this new way is revelatory. This mix is found on the more recent Feel Flows, a box set that compiles Surf's Up and Sunflower along with outtakes and other mixes from that era. The set also features an a capella mix of "'Til I Die," a piano demo, and the original, all of which allowed me to fully immerse myself in the song.

I can footnote this and point out that this Pavement reference (which also foreshadows, somewhat, the fourth footnote if you are paying attention) has become a favorite way to describe whatever it is this is.

Yes, this is the same year that “Two-Lane Blacktop” was released, which explains why the then-newly prolific Dennis Wilson contributed no songs to the album.

Listening to "Surf's Up" reminded me of a little vocal nod to the Beach Boys' track in the song of a younger artist, but, I'll be damned if I can find it. I was sure it was something on Cardinal's debut album, but even after the pleasurable experience of listening to it twice through this week, I couldn't locate it.

However, I was reminded that "Last Poems" from that album begins with the same lyric as the Beach Boys' "I Can Hear Music":"This is the way I always dreamed (Cardinal substitutes "knew") it would be, the way that it is…" before Cardinal veers in a different lyrical direction.

That had already come to mind this week when listening to the latest album from the Melbourne band Quivers, whose song "Apparition" builds its pre-chorus on a nod to Pavement's "Shady Lane." The original slackers sing "Oh, my God, oh, your God, oh, his God, oh, her God. It's everybody's God, it's everybody's God…" while Quivers offer "Oh my God, oh my God, oh everybody's God, everybody's got a reason…" Both this and the Cardinal lift are nice little Easter eggs to reward the attention of the faithful.

Of interest to perhaps only me (as if we hadn’t already reached that destination), while that earlier nod from Cardinal seemed like a reference to a then-ancient song, the temporal distance between the Beach Boys and Cardinal was 23 years, while that between the still recent-feeling Pavement and Quivers is 27 years. It's almost as if the passage of time folds in on itself as one ages.