I go back so far I'm in front of me

Looking at a handful of books of collected lyrics and musing on their value to a listener

When I started this Substack, I fully intended to repost some things I had tossed into the void that was my irregular, rarely visited Tumblr… then I started to write new material and promptly forgot that plan. But a recent conversation about Paul McCartney’s Lyrics: 1956 to Present, and the fact that I’m currently reading the Steve Wynn memoir I had wished for in this piece from 2022, made me dig this out and share it. Read on for a bit about books of collected lyrics.

Though I am a big music fan, and several shelves in my house are dedicated to books about music and/or by musicians, I don't own nor have I read many books of lyrics. They seem superfluous. Few song lyrics are strong enough to stand alone when divorced from their music, and I'm not sure why you would ask them to do so.

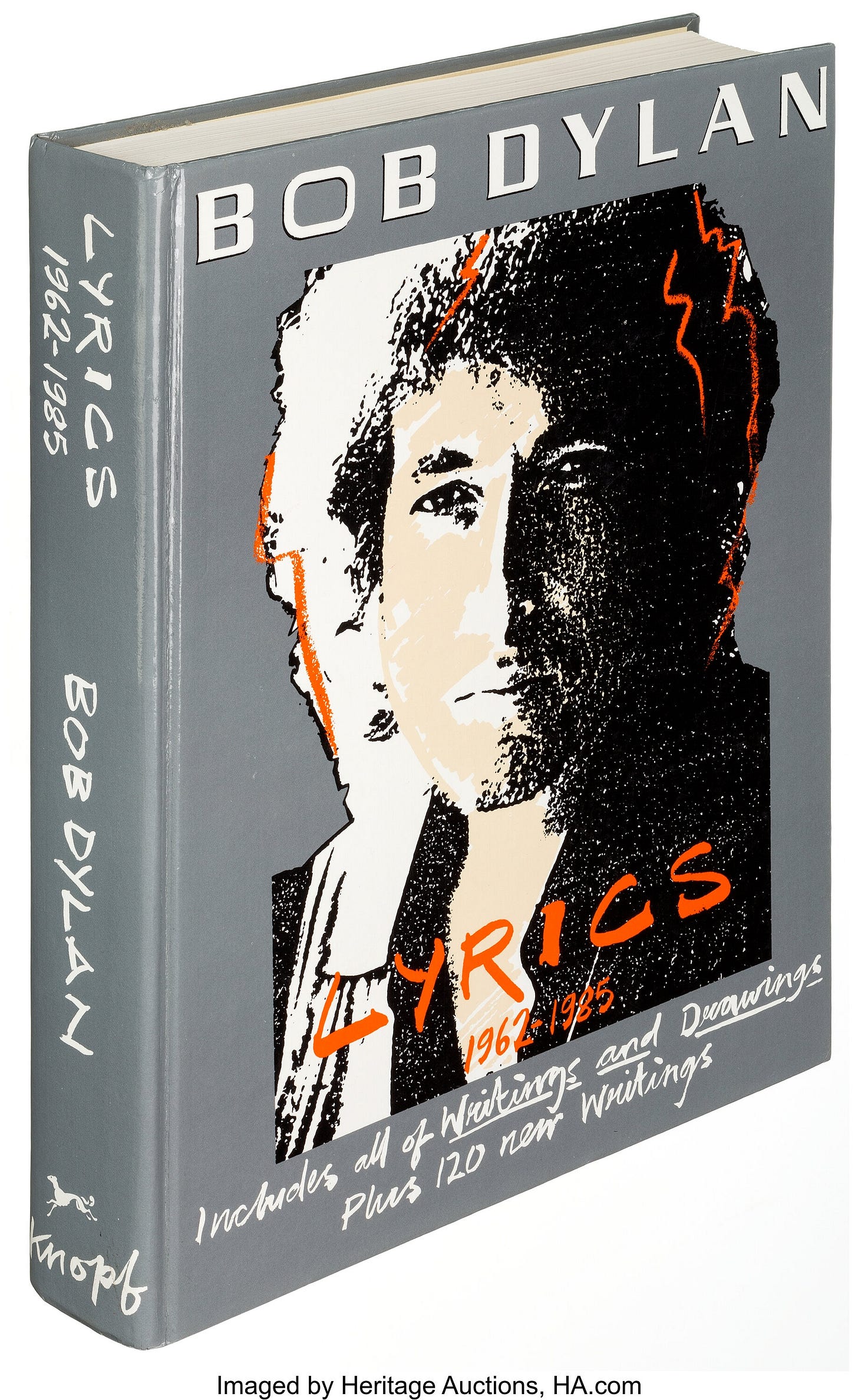

Despite this, I do own a few. One, of course, is a collection of Bob Dylan lyrics, the one that stops in 1985. I bought it as much for the extraneous things it includes, such as old liner notes and sketches, than for the lyrics themselves. Still, in this case, seeing the lyrics alone does help to emphasize things I missed when listening alone. I usually listen for the music, only paying attention to the lyrics after I have lived with a song long enough for them to really grab my attention. That goes for Dylan as well. Were I not captivated by his melodies and arrangements, his lyrics alone would not be enough to make me a fan. This extra reading — as is the case with the 20 or so Dylan books that fill a shelf — add context that makes me appreciate him all the more.

The second and third lyric books I own are by indie artists, for lack of a better term. Steve Wynn, singer and songwriter for the Dream Syndicate (who had a wonderful two-decade solo career before reforming that band); and Mark Lanegan, singer for the Screaming Trees (who continues to have one of the most interesting careers in rock music1). Wynn's was an automatic purchase. I'm a big fan, and pretty much support whatever he does. I found Lanegan's a few years after it was released while searching for his memoir, Sing Backwards and Weep. I knew I wanted to read that, and when I saw he had a lyric book as well, I Am the Wolf, I figured it was more than I needed.

Then I read the first lyric in the book, from the lead track on his debut solo album, The Winding Sheet. That song, "Mockingbird," was always a favorite, a brooding, acoustic tune that showed there was more to this long-haired, gravel-voiced rocker than had previously been revealed:

Your voice is a mockingbird

Calling me when the day is gone

You please yourself with every word

Telling me where I'm going wrong

Telling me where I've gone wrong

I realized these songs were deeper, more nuanced than I had previously thought, and knew that reading the lyrics while listening to the albums would unlock a new level to this music, making something I already enjoyed that much more resonant. Commentary about each album — something that Wynn's book features as well — was enough to seal the deal. Lanegan's book was an enlightening complement to his memoir, and now I eagerly hope for a similar book2 from Wynn to serve as a companion to his Complete Lyrics 1982-2017.

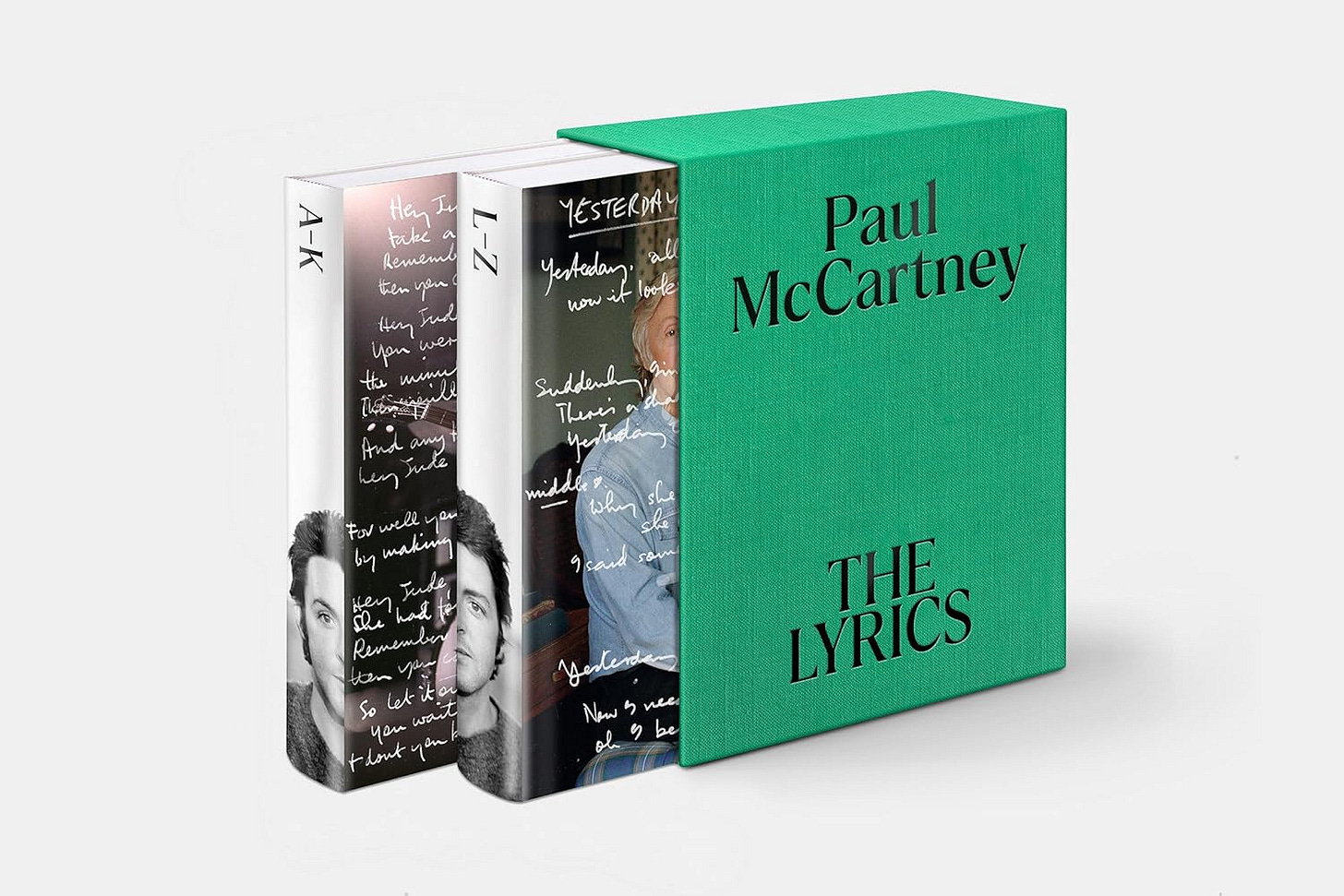

But I'm here because of Paul McCartney's The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present, a massive, two-volume book that is as close to a memoir as we're likely to see from the cute Beatle. This was a library acquisition, as I can't imagine reading it more than once and I couldn't justify the $100 price tag. I started with volume 2 thanks to fumbling the hold list at the library, but because everything is in alphabetical order, I'm not really missing anything save for Paul Muldoon's introduction.

When I brought it home, I figured it would be interesting to look at the photos, read a few of his commentaries about favorite songs, and then be done. But I've found myself reading it cover to cover. McCartney selected 150 songs, so it doesn't include everything. It does feature most of his Beatle favorites, of course, but also a smattering of tracks from Wings and his later solo records that might have (definitely, in my case) escaped notice. I found myself calling up a song on YouTube and listening while I read the lyric and his write up. After doing this for a the first few, I settled into that pattern for the long haul. Some of it is rather banal, but much of it is insightful. Despite having penned several tracks that any of us could quote from memory, McCartney is not a terribly talented lyricist overall; his real talents lie in melody and arrangement. He wrote "Silly Love Songs" because he loves and excels at writing rather cloying, somewhat embarrassing tunes about affection. That this sentiment was expressed in perhaps the most cloying, somewhat embarrassing tune of McCartney's career is really on the nose.

But for every few songs I sped through because my suspicions and biases were confirmed, there was one that had me tapping the "repeat" button. Sometimes it was the story behind the song, sometimes it was hearing something I hadn't previously thanks to McCartney's insights, and sometimes it was simply because I hadn't heard a song that I would have liked no matter when I first heard it.

Some of this is about hearing the right song at the right time. When I first heard "The World Tonight" from 1997's Flaming Pie, I'm sure I pushed scan on the radio to find another station. Today, 25 years after it was released, I hear a tightly arranged rock song with a solid guitar hook and a catchy melody that doesn't sound dated in the least. Context is everything. At the time, McCartney was 55 and more than three decades into his career. I'm sure I wasn't alone in asking, "Does the world really need more Paul McCartney?" Now, hearing it for the first time in more than two decades with my 52-year-old3 ears, it takes all my power to not wave my fist at the heavens and yell "Why don't they play music like this on the radio anymore?"

I still have little use for Wings, and McCartney's late-career clunkers outnumber his gems by a considerable margin, even in this hand-selected sample. But those gems are there to be found, and as much as the "writing about music is like dancing about architecture" line is bandied about, it's a foolish notion belied by books like this. As with anything, the perspective of an educated ear — or that of the creator and/or performer — can add significantly to the experience of listening. Words about music in the absence of that music are near meaningless at best, maddening at worst (how many songs have I read about and absolutely pined to hear because of the way they were described? (and how many lived up to the hype?)). But together, as I sit at my computer with YouTube cued up and McCartney's The Lyrics in my lap to read along, it is a rewarding experience4.

Lanegan died three weeks after I first posted this in early February 2022.

Ask and you shall receive. Wynn published his memoir, I Wouldn’t Say It If It Wasn’t True late last year.

Now at 55, the same age McCartney was then, this is even more true.

I was reminded of my previous post that included some tidbits from the “Beatles ’64” documentary on Disney+, including a quote from McCartney when asked by a reporter, "What place do you think this story of the Beatles is going to have in Western culture?" McCartney says, "Western culture?" and then laughs. "I don't know. You must be kidding with that question. Culture? It's not culture." "What is it?" he is asked. He responds, "That's a good laugh." His views have clearly evolved to the point where he very much takes seriously the notion that the Beatles music was important to the culture, or at least is willing to allow others to do so with his enthusiastic endorsement, if his comments to Muldoon here are any indication.