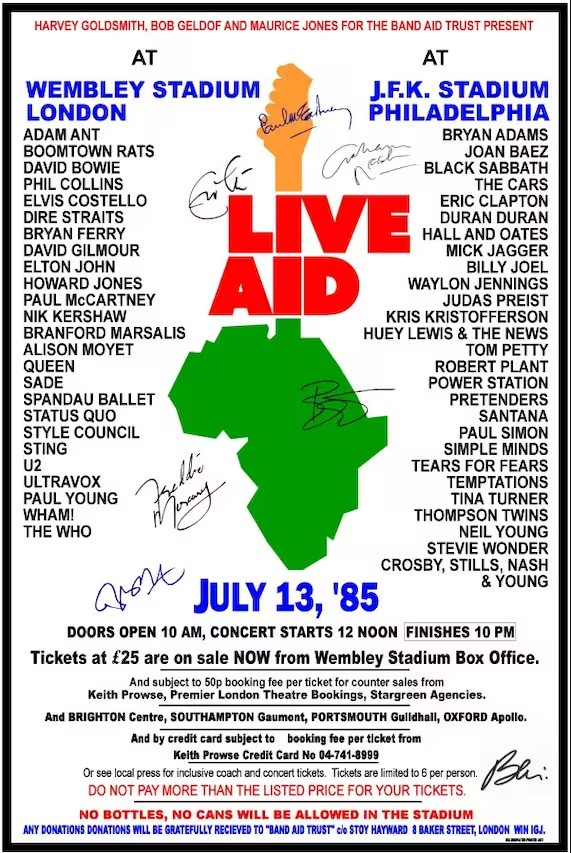

40 years later: Revisiting Live Aid

Four decades ago today, some of the biggest names in rock joined to raise money to combat famine in Africa. Here is a look back at some sets that blew my teenaged mind, and a few I missed

We remember where we were for major historic events: The day John F. Kennedy was shot, the day the Columbia space shuttle exploded, or on Sept. 11, 2001. But good things spark memories as well, and I remember clearly where I was on Saturday, July 13, 1985: I was in the basement of our house in Des Moines, VCR remote in hand, ready to press “record” each time a favorite act took the stage at Live Aid.

Today, you can watch and piece together videos of the entire event online with the press of a button. In fact, today, July 13, 40 years to the day of the original concert, you can watch newly packaged videos of that historic event all day long as they debut on YouTube across the course of the morning and afternoon. But back then, you had to keep your family away from the television so you could keep the dial on MTV. You had six hours of recording time on a VHS cassette, so you had to be judicious. For me, that meant superstars and those in waiting. Over time, I have become a big fan (and puzzled over the performances) of artists like Neil Young and Bob Dylan, but that day it was all about high wattage.

As a 15-year-old who was quickly falling under sway of pop music, it was exhilarating to see so many performances as they were happening, to be a part of a shared experience with an estimated 1.9 billion people in 150 countries (according to the Live Aid Wikipedia entry, that was 40 percent of the world population at that time). This was a big event, and it felt special to be watching, even if that meant cocooning myself in a basement on a hot summer day.

It started at 6 a.m. here in Iowa, with acts taking the stage at noon in Wembley Stadium in London. I know I wasn't up that early. Sting, with a 3 p.m. slot at Wembley and an early 9 a.m. appearance on my TV, was probably the first artist I paid attention to, as my Anglophilia was limited at the time (sorry Style Council, Status Quo, Ultravox et al). Dream of the Blue Turtles had been out for less than a month, so I am sure my fandom was at a fever pitch.

Phil Collins joined Sting for his set, performing a couple of his own songs as the two sang backing for one another. Seeing these two together would have been next level. No Jacket Required was in constant rotation with Dream of the Blue Turtles in my cassette deck that summer, so the two dueting on "Long, Long Way to Go," with Branford Marsalis on soprano saxophone, might have been a peak experience.

That is, until U2 took the stage. The same outing where I bought No Jacket Required also yielded Wide Awake in America.1 My tastes were rapidly evolving that year and into the next, and U2 was a gateway to more of what was dubbed “college rock.” This was my first chance to see U2 beyond "Under a Blood Red Sky." The band’s performance here of “Bad” might have been the iconic turn of the entire festival had it not been for Freddie Mercury and Queen an hour later. Bono jumped down to crowd level to pull a woman from the scrum as she was being crushed by the masses, then danced with her as the band stretched the song past the 11 minute mark.

It was a day of grand gestures, perhaps none more potent than Mercury, in full control of the 72,000 people in Wembley Stadium as he led them through acrobatic voice exercises before capping their set with “We Are the Champions.” On a day where a reunited (for the first of many times) Who, an ascendant David Bowie, and a superstar Elton John were still to come, the high point may well have been at 7 p.m., hours before the concert closed its UK segment.

The broadcast switched back and forth throughout the day as those London performances were joined by those from Philadelphia. The Hooters, with a prime 9 a.m. slot probably earned a few inches of videotape from me as they played a couple of their ubiquitous hits, and then it would have been tough to compete with the UK’s stacked lineup as Rick Springfield, REO Speedwagon, and Judas Priest took the morning stage from Philly.

Had I been more knowledgeable at the time, I would have paid more attention to things like the improbable reunion of Black Sabbath with Ozzy Osbourne,2 what must surely have been one of the first national TV appearances by Run DMC, a set by the Beach Boys with Brian Wilson, a stripped down “The Waiting” from an impressively mutton-chopped Tom Petty, and an eclectic performance by an also impressively mutton-chopped Neil Young.

Instead, I know I was indifferent to those as I waited for Simple Minds, Duran Duran, The Cars, and Hall and Oates.3 I’d like to think I could have accelerated my musical evolution with one blast of Neil’s “Powderfinger,” but I know I wasn’t quite ready.

As the evening set in on the U.S. show, I remember feeling exactly as I was supposed to about Phil Collins transatlantic feat of performing in London, hopping on the Concorde and then doing it all again in Philadelphia. It was impressive, playing with Eric Clapton and Led Zeppelin in Philly in addition to his own set4. Jimmy Page and Robert Plant have subsequently disowned the Zeppelin performance (comparing this muddy “Stairway to Heaven” with something like the Who’s powerful “Won’t Get Fooled Again” at Wembley earlier in the day, I don’t blame them) , but it is still worth digging up (it’s not on Live Aid YouTube accounts or DVDs or any other official release because Plant and Page forbade it) for the historical value.5

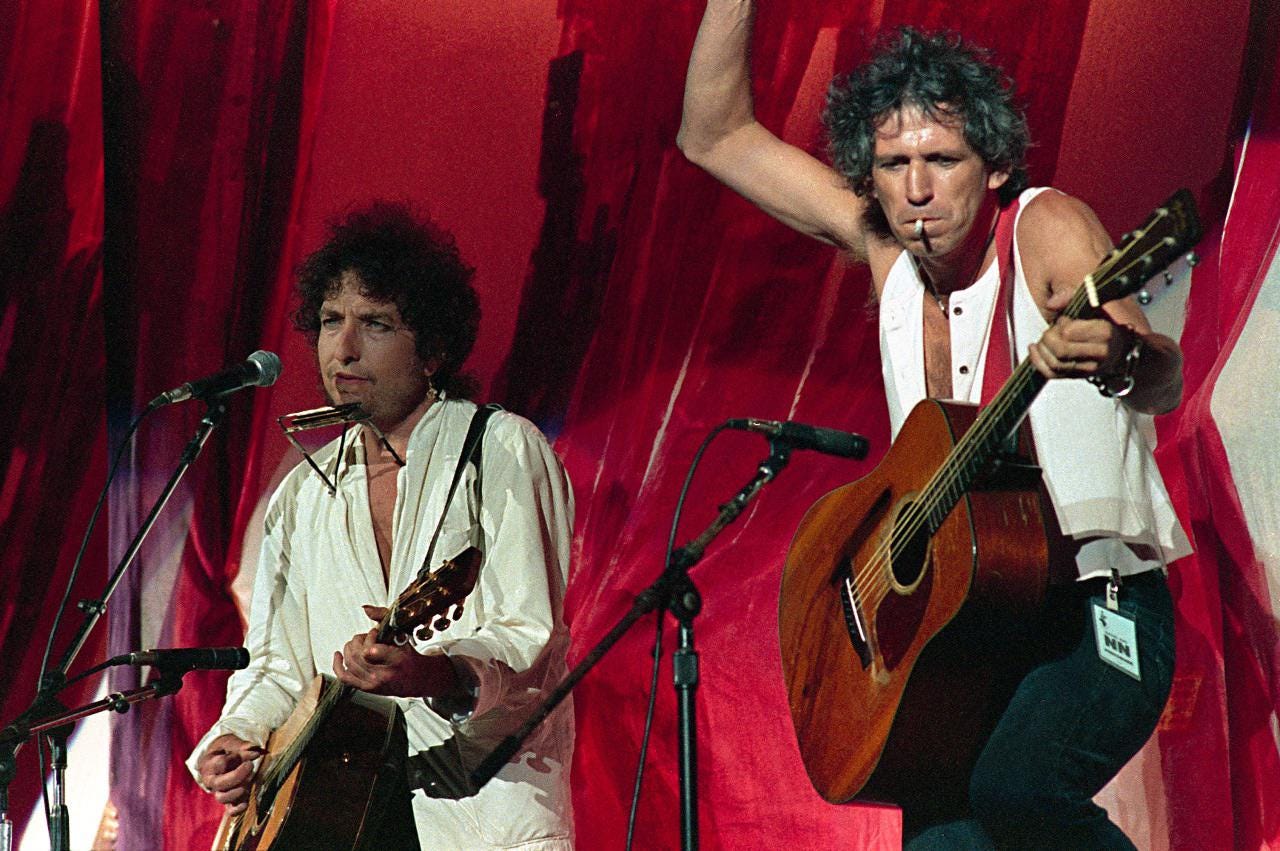

The one set I doubt I saw the first time, but the one I’ve watched and thought about more than any other in the years since, is by Bob Dylan. Joined by Keith Richards and Ron Wood, who don’t seem like they knew they were going on until that moment, Dylan performed “Blowin’ in the Wind.” After a day of transcendent, bombastic, and overwrought performances, it seems fitting that Dylan would subvert expectations with an out-of-tune ramble through three acoustic numbers. And of all the things said from the stage, from the inspired to the insipid, Dylan had the most impactful utterance: “I hope that some of the money that's raised for the people in Africa, maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe one or two million, maybe, and use it, say, to pay the mortgages on some of the farms that the farmers here owe to the banks.” It was criticized by Live Aid honcho Bob Geldof as tone deaf, but the result was Farm Aid, which debuted that September and celebrates its own 40th anniversary with a concert in Minneapolis this fall.

We live in a time where we can’t seem to agree what to believe in or what to fight for, and it would be naive to suggest the world was united behind the cause of combatting African famine in 1985. But it did seem for one day, sitting in a Des Moines basement, that I was part of something larger.

Geldof has said, “We took an issue that was nowhere on the political agenda and, through the lingua franca of the planet — which is not English but rock ’n’ roll — we were able to address the intellectual absurdity and the moral repulsion of people dying of want in a world of surplus.” There may debate about how much money was raised, what it was spent on, and how much good it did, but it did raise awareness and keep the issue in front of people. And it led to similar efforts that continue today, harnessing the power of performance to shine a light on areas in need of help.

So bask in nostalgia today watching 40-year-old clips of one of rock’s biggest days, but keep in mind the work that needs to be done tomorrow and in the days after around issues that may or may not reach your radar on the crest of a soaring vocal or a power chord.

And the debut from The Power Station… a nod to the (admittedly overbearing) sublime on one side of Phil in the form of U2, a nod to the (admittedly fun yet vapid) ridiculous in the form of Power Station on the other. And yes, Power Station performed, and I’m sure I watched, though Michael Des Barres had replaced Robert Palmer by that point, so I’m sure I wasn’t too excited.

A full circle moment as the band’s “Back to the Beginning” show last weekend found them performing for one final time.

Watching this set, where they featured Eddie Kendrick and David Ruffin from the Temptations, I was compelled to look up the ages of those ‘60s stars. Ruffin was 44 at the time, just five years older than Daryl Hall’s 39.

Why he played the same two songs at both shows is another puzzler.

I dubbed an audio cassette off of my videotape and listened a lot to the Zeppelin set, so much that any time I hear “Stairway to Heaven,” even today, when Plant reaches the “echo with laughter” part I still hear his ad libbed “Does anybody remember laughter?”

Two words: Sade.