Take Five: Reinvention

Everything is just a little bit different this week as I check in with Talking Heads, Nick Lowe, Al Green, Jessie Montgomery and more

“Take Five” is posted each Friday, and offers five things I spent some time with over the course of the previous week. No criticism, no in-depth analysis, just a few things I think you might be interested in checking out. When the spirit moves me, I’ll post other things at other times.

I didn’t set out to focus on reinvention this week, but everything pretty well fell into that category despite the lack of effort. From alternate takes to inspired thievery, soulful covers to (r)evolutionary performance, it was a week of building and growth.

1. Talking Heads — "Psycho Killer" with Arthur Russell on cello

It's usually the case that while the alternate tracks found on deluxe editions of classic albums are interesting, it is clear that the right decision was made at the time of release. I'm not sure that's the case with the version of "Psycho Killer" found on the Super Deluxe version of Talking Heads: 77. If push comes to shove, I suppose I would say the original has the right mix of playfulness and menace. However, this version, which includes the late Iowa native Arthur Russell on cello, adds so much. It doesn’t even feel like the same song, which might be why I like it so much. The original still exists, and this is something different altogether. Russell's strings add depth and texture to the track, and the guitars are more muscular as well, seemingly trying to hold their own against this new element. It's more accomplished as a recording, more fully realized, but I don't think the song would be the cult hit it has become had this been the definitive version. It needed that slinky menace. A note on the release: This was actually a part of the first expanded reissue of the album in 2006. But it eluded me then, so it's new now.

2. Nick Lowe — "Cruel to be Kind" on World Cafe

As a fan of Nick Lowe going on 40 years, I have heard his stories many times. But his recent appearance on World Cafe was the first time I heard him explain, with guitar in hand, how Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes' "The Love I Lost" inspired "Cruel to be Kind." He talked about how his early band, Brinsley Schwarz, loved the song, but it was too sophisticated for them to play. "We just murdered this song," he said. He offered to take the groove and write a song that the band could play. In the video above, he plays the Harold Melvin bass line and then shows how it informed the similar bassline for "Cruel to be Kind." The laid-back groove of soul music has always underpinned Lowe’s best work, so it is instructive to watch him explain the way he built on that foundation for one of his most enduring tunes. Keep watching above for a particularly spirited solo run through the classic.

3. Al Green - "Everybody Hurts"

I must admit, I have had a love/hate relationship with "Everybody Hurts" from the moment I first heard it. It's a simple pop song with a great Michael Stipe vocal, but the lyrics always seemed cloying and obvious, and for every time I would leave it on when spinning Automatic for the People, there were at least two times I would skip to "Sweetness Follows" (and several times when I wouldn't stop skipping until I reached "Monty Got a Raw Deal"... for a classic album, this does have a soggy middle). As I have aged, I have grown to appreciate the song a bit more, allowing the message to hit when I needed it, and slide off when I didn't. If everything eventually finds its true level, "Everybody Hurts" may finally have settled into its proper place in the hands of Al Green. Words that sound precious and twee from Stipe sound profound when intoned by Green. R.E.M. recorded their album in New Orleans, and there is a hint of that town’s vibe on some of the tracks. Green finds that here and polishes it, turning the song into an organ-driven testimony. “Recording ‘Everybody Hurts,’ I could really feel the heaviness of the song, and I wanted to inject a little touch of hope and light into it," Green said. "There’s always a presence of light that can break through those times of darkness.” Had things gone differently on Nov. 5, the timing of this release would seem odd. Unfortunately, it feels essential.

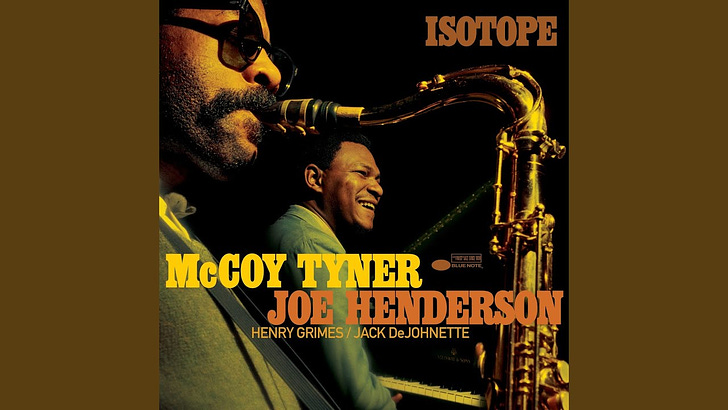

4. Joe Henderson and McCoy Tyner — “Isotope”

There are a finite number of unheard recordings from the peak post-bop jazz era, so when something new is found, it is cause for celebration. Such is the case for Forces of Nature, the new live album out today credited to saxophonist Joe Henderson and pianist McCoy Tyner. The recording comes from Slug’s, a New York jazz club, where the quartet — rounded out by drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Harry Grimes — was recorded in 1966. It was a pivotal time for the musicians. It fell during the time between when Tyner left John Coltrane’s quartet and recorded his wonderful solo LP The Real McCoy (which featured Henderson), while Henderson had recently left Horace Silver’s band. Though each was a well-known performer, perhaps there was a little something to prove here, and the result is a performance that has a bit more snap and verve than the recorded version. You can find that one on Henderson’s 1964 album Inner Urge. It’s a strong track that features Tyner’s piano (drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Bob Cranshaw round out the group on that session). But this one has more, and the rest of the album — created from a tape of the show that has been in DeJohnette’s hands for nearly 60 years — promises more of the same.

5. Jessie Montgomery - “Rhapsody No. 1”

I could write an entire post about seeing Jessie Montgomery perform last night with PUBLIQuartet at Hancher Auditorium, but I will limit myself to two things. The young composer’s work is playful and improvisational — two qualities not often associated with classical music. “I have this idea in my mind that there’s something beyond fusion,” Montgomery told the New York Times in 2021. “There’s this other sound I’m going for that is a culmination, like the smashing together, of different styles and influences. I don’t know that I’ve achieved that yet.” I believe she has. “Jessie’s Lullaby,” a tune written by her mother, Robbie McCauley (and published in Broadside in 1983), is a few bars long, but was stretched into several minutes of overlapping exploration as Montgomery and the four PUBLIQuartet members nudged one another through myriad interpolations of the simple melody. It was gorgeous and a highlight of the night. Earlier, Montgomery took the stage alone to perform “Rhapsody No. 1,” her first solo composition. As explained in the program notes, it “requires a number of non-traditional or extended techniques from the performer,” all of which made the piece feel unlike anything else I’ve heard performed under the “classical music” umbrella.