Take Five: Finding refuge in art

It was difficult to concentrate with the country collapsing around us this week, but I did find the occasional respite in music, fiction, philosophy and poetry

“Take Five” is posted each Friday, and offers five things I spent some time with over the course of the previous week. No criticism, no in-depth analysis, just a few things I think you might be interested in checking out. When the spirit moves me, I’ll post other things at other times.

What a week! With no patience for the post mortem and infighting that is sure to result from Tuesday’s disaster, I retreated, seeking solace in the usual places. Books and music offered a balm, though in many instances, things I encountered seemed to comment on current events.

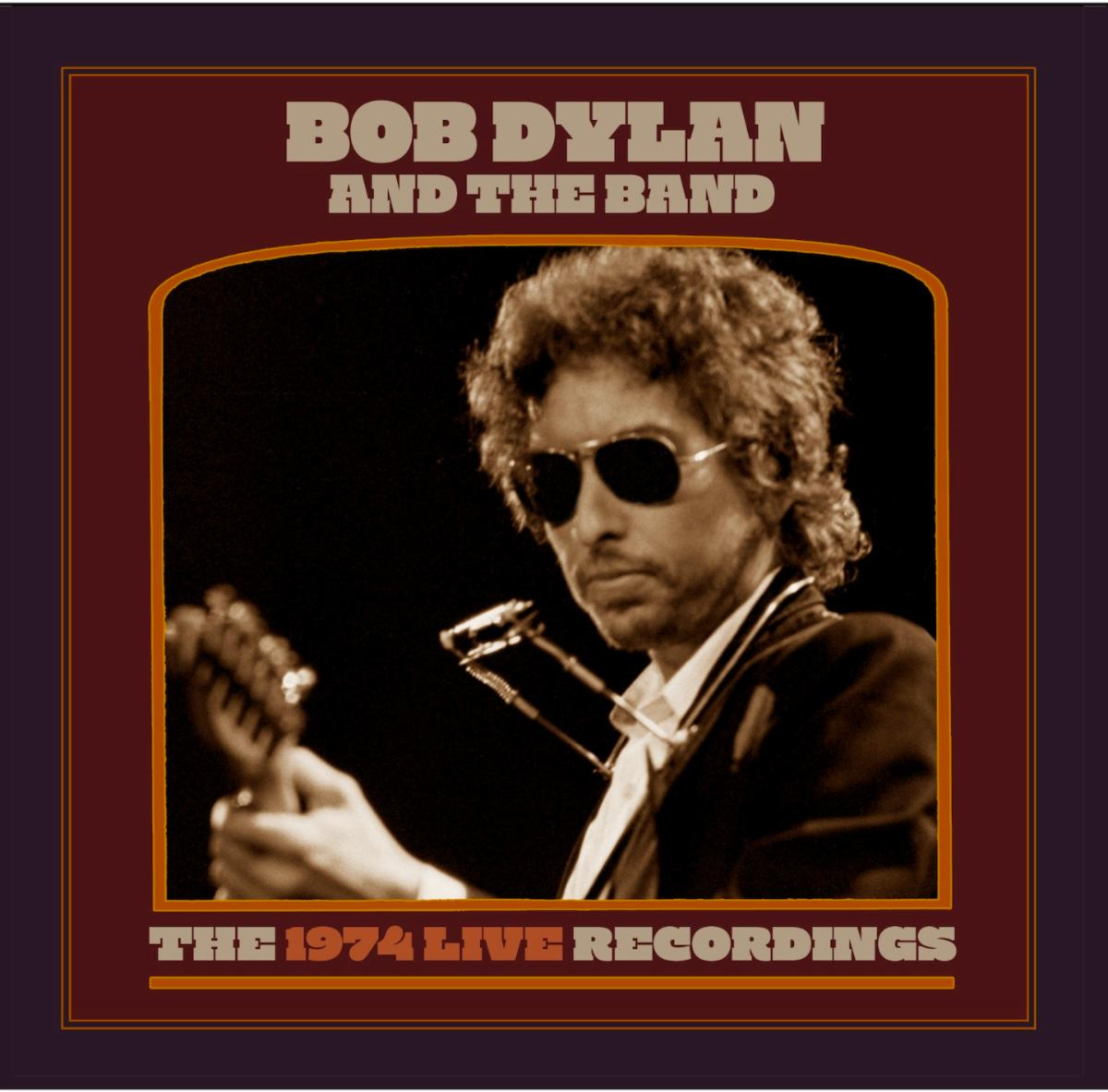

1. Greil Marcus on Bob Dylan

On the occasion of the release of Bob Dylan and the Band’s 1774 Live Recordings set, Greil Marcus revisited his original review of Before the Flood from the Village Voice. One section caught my eye:

When I listen to the radio today, I hear Paul McCartney, Elton John. At home I play Steely Dan's Pretzel Logic, Roxy Music's Stranded, and Roxy singer Bryan Ferry's strange new oldies album, These Foolish Things (he does "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall"; he also does "It's My Party"). Before the Flood exposes the calculation of these records. They are so well-made, either in terms of simple production (Paul and Elton) or a whole vision of popular culture (Steely Dan, Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry) that they leave almost no room for the listener to create. The tension between musicians and audience is proscribed; your responses have been figured out, and if the artist is good at his job, you go where he wants you to go.

This obviously wasn’t what Marcus had in mind when he wrote this in 1974, and he wouldn’t necessarily agree with it now, but this perfectly encapsulates why I fell in love with Guided By Voices and other "lo-fi" bands and bedroom pop artists. In fact, while I do love some incredibly well produced music — I'll never turn off Boston when it comes on the radio, and pristine power pop is a perennial favorite — you could extend this to nearly everything that appeals to me across art forms. From indie cinema to expressionist painting to lo-fi music, I most appreciate art that meets me halfway rather than presenting a neatly wrapped, finished product. It also is one of the many reasons why I don’t like Steely Dan.

2. Ava Mendoza - "Pink River Dolphins"

Ava Mendoza was a featured artist at FEaST, an Iowa City music festival I helped out with this year, and so the first time I heard "Pink Dolphins" was when she performed it live last week. She played solo, her guitar overpowering her vocals, making them more a shading than a feature. I didn't mind; Mendoza is one of the most inventive electric guitars on the scene. In this show, as on her new solo album, The Circular Train, Mendoza starts most of the songs playing what feels like a fairly standard figure: A blues riff here, a bit of finger-picked folk there. But these feel like the artist telling the audience, "Yes, I can do that, but we'll both find it more interesting if I do this," as she heads into uncharted territory. The song's title made me wonder if there was a connection to the late trumpeter Jaimie Branch's album with Anteloper called Pink Dolphins. Indeed there is. Mendoza, writes in the liner notes for The Circular Train that she and Branch shared a love of the animal. Mendoza is half Bolivian, while Branch was half Colombian, and pink dolphins are found in both countries. So while the song is a tribute to the titular creatures, it also serves as a nod to the departed trumpeter.

Better able to hear Mendoza sing on the album version of the song, I'm reminded of the less-polished vocals of artists like Patti Smith or Sleater-Kinney's Corin Tucker. Both have an untrained sound that carries so much passion, and Mendoza's lyric about the dolphin's use of echolocation shines through in similar fashion. While I love her playing and am content to hear as much instrumental music as she can offer, I do hope we hear the occasional vocal in the future.

3. Garth Greenwell on Kant's "kingdom of ends"

I haven't spent much time studying philosophy, so when I come across something of interest, it is almost always new. Such was the case while reading Garth Greenwell's Small Rain (yes, I'm still slowly making my way through while reading six or seven other books at the same time). His protagonist, confined to a hospital bed, contemplates a particular poem that he has taught often.

"If it’s true, what Kant says about the kingdom of ends, I used to say to my students, if it’s true that standing in an ethical relation to another means recognizing that their life has exactly the same value as my life, as the life as those I love, which is to say immeasurable value, boundless value: if each life… makes a claim upon the world, for resources, possibility, regard, love, that is infinite in its legitimacy, if each of the billions of human lives has that much value, then of course we can’t bear to live in that kingdom, in the full awareness of all that value."

The character continues, but that was enough to set my head spinning. I read this the day after Election Day, a day that was among the most demoralizing and depressing in memory, a day when 72 million Americans clearly did not recognize that every other life has the same value as their own. It's a heady thought, this "kingdom of ends," and it led me to look up a bit about that particular aspect of Kant's work (which is another reason why it is taking me so long to make my way through Small Rain). I soon got bogged down in Kant's "categorical imperatives," but perhaps I'll be motivated to do more digging by, of course, reading a book by or about Kant.

In the meantime, it is Greenwell that has me thinking more deeply. His character offers perhaps the most salient point as he continues his discourse about Kant, saying it would be debilitating to see the billions of other lives on the planet as anything other than abstractions, to grant their sufferings the priority you grant your own. Thinking of the election, however, one feels that there is step short of that, to simply grant others the grace to live their lives as they see fit while not allowing your own pursuit of such an existence to impede that of others.

4. Gene Clark - "Full Circle Song"

Much as Greil Marcus wasn't talking about lo-fi pop back in 1974, Gene Clark wasn't commenting on the 2024 Presidential Election in 1972 when he penned "Full Circle Song." Yet the tune, which popped up on shuffle this week while I sought out comforting music, nevertheless spoke to my feelings as much as anything.

Funny how the circle turns around

First you're up, and then you're down again

Though the circle takes what it may give

Each time around it makes it live again

The erstwhile Byrds leader wrote the song for an aborted 1972 solo album that eventually saw the light of day in the Netherlands as Roadmaster. He brought it to a Byrds reunion the same year, recording it with the original quintet. Both versions came out in 1973. I prefer the Byrds version, if for no other reason than that it's hard to compete with those high harmonies from David Crosby.

This election is going to sever relationships, as wounds that may have scabbed over in 2020 were reopened as people opted for division and chaos despite knowing the harm it will cause. One hopes Clark is prescient, that wisdom will prevail and healing can take place on the other side of this.

Funny how the circle is a wheel

And it can steal someone who is a friend

Funny how the circle takes you flying

And if it's it right it brings it back again

5. Layli Long Soldier and Lyuba Yakimchuk poetry

I finished two poetry books this week that I had been slowly making my way through over the past month, dipping in when time and my psyche allowed. As often happens, they slowly slipped into dialogue with one another. I picked up Apricots of Donbas by Ukrainian poet Lyuba Yakimchuk after hearing her on a panel discussion as part of the University of Iowa's International Writing Program. Though its 2021 publication predates the ongoing assault by Russia, its recounting of the Russian attacks in the Donbas region that began in 2014 show how cyclical, ongoing, and relentless that constant state of war has been for Ukraine. A standout is "Decomposition," where Yakimchuk deconstructs words as they stand for places in Ukraine destroyed by war.

don’t talk to me about Luhansk

it’s long since turned into hansk

Lu had been razed to the ground

to the crimson pavement

Layli Long Soldier's Whereas, a National Book Critic's Circle Award winner in 2017, finds the Oglala Dakota poet writing about U.S. treatment of Native Americans. A significant portion of the book stands as a response to the little-known apology to native people signed by President Obama in 2009, while the long poem, "38," tells of the hanging of 38 Dakota men approved by President Lincoln the same week he signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

This is heavy, important work. These collections were not easy to read, nor should they be. But as the parallels between the two collections revealed themselves, something deeper resulted, a new context. In both cases, fact-based verse offers a way to interpret and understand events that would be more difficult to absorb in straight up prose. Yakimchuk and Long Soldier bear witness, and their accounts will leave you feeling — angry, frustrated, and ashamed, yet hopeful because they are here to share their work, and opened eyes may yet chart a different course.