Synchronicity at 40

A super mega post about The Police then and now, with 33⅓ book pitches, a live review from 2007, and thoughts on Stewart Copeland's latest reimagining of the canon

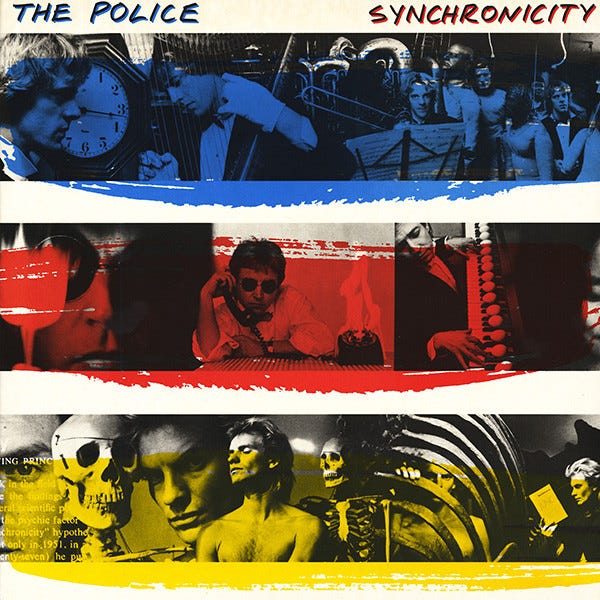

In the ever-expanding category of album anniversaries that make me feel old, I present Synchronicity by the Police, celebrating its 40th anniversary this month. Learning of that milestone, I was reminded of my attempt -- or, as I was surprised to recall, attempts -- to pitch a book on the album as part of the "33⅓" series of books about albums. The publisher held open calls (and maybe still does… I finally gave up), and I submitted four pitches over the years. I tried The Jayhawks' Hollywood Town Hall in 2005, Synchronicity in 2007 and 2009, and Richard Hell's Destiny Street/Revisited in 2012. With the second Synchronicity pitch and the one about Hell's album, I made it to the second round, but all four attempts eventually failed.

Given that these have been sitting on my hard drive for the past 15-plus years, I figured perhaps this anniversary was a good time to dust them off. What follows are those two Police proposals --first the 2007 pitch, and then the updated version from 2009. There is a little overlap, so you can skip if you like, or see how I refined things. In between, the band reunited for a tour, and I had the chance to see them at Wrigley Field in Chicago in 2007. That certainly made the second pitch more viable. My blog review of that show follows the two pitches. I close with a short review of drummer Stewart Copeland's brand new album, Police Deranged for Orchestra.

2007 33⅓ pitch

In an interview long after the fact, producer Hugh Padgham told MixOnline magazine that the Police’s Synchronicity was one meeting away from not happening. “I remember… ringing up my manager and saying, ‘I hate this,’ because sometimes the tension in the room was so horrible,” he said of the recording sessions. “But in many ways, that tension is what ended up making such a good album.”

At its root, Synchronicity is the product of creative friction, something that clearly led the Police to its greatest heights artistically and ultimately led to its demise. Publicly, the band stayed together until 1986, after a handful of live dates in support of Amnesty International and a trip to the studio to re-record some hits for a best-of compilation. But for all intents, the trio split at the end of their 1984 world tour.

In my book about Synchronicity, I will take an in-depth look at the creation and recording of the disc, putting it into context both within the band’s discography and the pop music of the time. I will analyze the three members’ careers as they reached this point and then moved beyond it. The book will also include a short song-by-song analysis of the album, looking particularly at the lyrical inspiration Sting found in the works of Arthur Koestler, Paul Bowles and Carl Jung.

The unrest within the band is well known; interviews with Sting, Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland in the run-up to their 2007 reunion often centered on the perceived hatred among the three. Using the auto-summarize function on Microsoft Word on a document containing nearly a dozen interviews with the band, I came up with this summary:

Sting: Shut up, Stewart.

Stewart Copeland: You bastard!

The truth is far more complex, however, and the tension was as positive a force as it was negative. Regardless of what drove them to split, before they did, the three recorded a disc that elevated them to the pinnacle of pop. It was among the five best-selling discs of 1983, spawned four big hits – including the eternal (and eternally misunderstood) classic “Every Breath You Take” – and led to a mega-selling worldwide tour. It occupied a strange place at the top of the chart, displacing the soft soul of Michael Jackson’s Thriller before being replaced itself by Quiet Riot’s Metal Health. It was perhaps the only time that pre-emergent pedophilia, Jungian philosophy, and mullet-fueled rebellion were so cozy in the world of pop music.

The downside of the friction within the band still can be seen in a positive light, because it certainly fueled the decision to go out on top. Consider how rare that is. At the end of the band’s set during the last Amnesty International “Conspiracy of Hope” concert in Giants Stadium in 1986 – its last show before officially splitting – Summers handed his guitar to U2’s The Edge as that band took the stage. In the introduction to Summers’ memoir, One Train Later, Edge writes, “I certainly will never forget the moment Andy handed me his guitar in front of the 65,000 capacity crowd at the end of the Police’s final set, for U2 to play out the last song of the event. There was more than a little symbolism in that handing over of instruments.”

What if U2 had not only taken up the mantle as the world’s biggest band – something it would accomplish the next year with The Joshua Tree – but then, like the Police, hung it up and went their separate ways? There would be no Achtung, Baby, of course, but also no Pop. Few in any discipline, be it music, sports, or business, are willing to chance that their best days are behind them. But faced with the near certainty that their subsequent releases would be hits, that they could do anything they wanted and remain successful for the foreseeable future, the Police instead chose to split.

In doing so, they encased the disc and the band itself in a figurative chunk of amber, protecting their legacy from future transgressions. I still remember walking into the Younkers department store on the south side of Des Moines to pick Synchronicity out of the album racks. I was 13 and played the album on a near-daily basis for the next 18 months. Whenever I pop in my CD version today, "Synchronicity I" still sounds strange without the five seconds of needle noise that preceded it on my turntable.

When I return to the album, everything – save for the pops and clicks – is the same; there are no later flops to make me wish they had split sooner. My own tastes have changed, my perspective broadening considerably in the intervening 25 years, so I realize there is plenty of filler on this and the band's other four albums. But I still enjoy the songs and admire the trio's musicianship. My subsequent understanding of the dynamics within the band only enhances that admiration.

In addition to drawing from contemporaneous and current sources of information, including books by the band members, films, interviews, and other material, I plan to conduct several interviews for the book. I hope to interview all three band members, but I can rely on the wealth of interviews given over the band’s career and beyond should that prove problematic. I also will interview people close to the band, such as Padgham, live techs Danny Quattrochi and Jeff Seitz, manager Miles Copeland and others. Within the song-by-song analysis I plan to use material gathered from interviews with writers and perhaps a Jungian scholar discussing Sting’s lyrics. I will talk with a musicologist like Daniel Levitan about the way these three created something unique and how the resulting sound appealed to the masses. I also plan to interview photographer Duane Michals, who helped to conceive the 36 variations in the album’s cover art.

2009 33⅓ pitch

One could argue that Synchronicity was a commercial lock. Each of the Police’s four previous albums sold better than the last, spawning bigger hits and more media attention. It was released less than two years after the advent of MTV, and videos featuring the band’s broodingly handsome front man, Sting, were in constant rotation. Its most-popular songs are so well-constructed they still sound fresh today. Given that, its 18 weeks at No. 1 during 1983, three Top 10 singles and three Grammy Awards seem practically pre-ordained.

Yet one could just as easily argue that it is the most unlikely blockbuster of the past 30 years. Sting, Stewart Copeland and Andy Summers, in their 30s and 40s by this point, were moving out of their prime as pop stars. Their music had shed much of its playful reggae lilt in favor of a more sophisticated jazz-rock groove, and Sting’s lyrical occupations made the songs feel at times like high school literature lectures. The first side included two songs about Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity with lyrics lifted directly from his writings, one about the fate of the dinosaurs, another calling into question God’s laissez-faire approach to the world’s suffering, a screeching bit of shout therapy about the guitarist’s Mommy issues and a ditty from the drummer about Soviet-era politics.

Never mind that the band members hated each other, and that Sting clearly ached to embark on a solo career.

Such a book will be unique in the marketplace, for even though the band has remained wildly popular over the 25 years since Synchronicity – it had the highest grossing tour of 2007 and the combined receipts of that tour topped $350 million with more than 2 million tickets sold – there are few books about the group and almost none from a current perspective. Those that exist are terribly dated and often offer little more than hero worship of Sting and a cursory look at the Police’s career for context.

The band was well covered in the lead up to the 2007-08 reunion tour, yet most treatments of the band continued to focus on the rancor among the trio to the exclusion of nearly all else. This tension was certainly present and was a key driver in creating Synchronicity. In an interview long after the fact, producer Hugh Padgham told “MixOnline” magazine that the album was one meeting away from not happening. “I remember… ringing up my manager and saying, ‘I hate this,’ because sometimes the tension in the room was so horrible,” he said of the recording sessions in Montserrat. “But in many ways, that tension is what ended up making such a good album.”

To focus solely on this aspect of the band and the recording of its biggest album, however, misses several key points. Of far greater importance is the combination of creative elements that balance each other within the band. It is because of, not despite this combination of both positive and negative traits that led to the album’s success and continued relevance. Elements that might otherwise have canceled each other out instead seemed to elevate the album. Sting’s lyrics were rightly criticized by some as preachy and at times annoyingly didactic, yet they were carried by indelible melodies that found teenagers singing along as the former teacher sang of Jungian philosophy. The jazzy flourishes could be seen as excessive and off putting, yet they were always played in service to the song and surely attracted some who searched for more than Quiet Riot and the Flashdance soundtrack could offer that year.

Rock critic Robert Palmer summarized this duality in a New York Times piece about the album, comparing it with the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band: “For Sgt. Pepper is a rock paradigm, a successful group’s eagerly awaited album which takes big chances, demands serious attention but also sells millions of copies. Synchronicity isn’t the first album since Sgt. Pepper to re-create this balance, to have its finger so firmly on the pulse of the times that it manages to be genuinely avant garde and genuinely commercial at the same time. But it doesn’t happen very often, especially these days, and the fact that the Police have made it happen again is a cause for rejoicing.”

Of course, the Police made it happen exactly once, for Synchronicity proved to be the trio’s swansong. Despite abortive attempts in 1986 to work on new material, it was clear that Sting’s solo career was well under way and the Police were through.

“I wanted no rules, no limitations,” Sting later said of that time. “Bands that stay together have to toe the party line. And I wasn’t willing to do that. We were the biggest band in the world, by all intents and purposes, and I just thought: ‘Well, this is it. After this everything else is just diminishing returns. I want another challenge. I want to start again.’”

By exiting, Sting ensured that the Police went out on top in a way that few other bands have, but it put him in the untenable artistic position of dictator. No matter his commercial success as a solo artist, Sting’s output without Copeland and Summers is too often frustratingly dull, adult-contemporary pop that lacks the fire and inventiveness of his work with the Police. Without the push, pull and, at times, literal punch of his band mates, Sting’s music is overly fussy. What Sting wanted, and what Sting needs, are two different things.

“I’m now in a band where I can’t fire anybody,” he said in an interview included in the Police’s reunion tour concert DVD “Certifiable” from 2008. “I can’t fire anybody. So I’d better negotiate. I’d better argue my case. I have to present things and be diplomatic for a change.”

He seems to see this as a bad thing, but in fact it is the very dynamic that made the Police – Synchronicity in particular – so good. Sting’s most enduring song, “Every Breath You Take,” was improved immeasurably by Summers’ Bartok-inspired guitar line, while Copeland’s gleeful prodding of his bass player rankled and sparked Sting to creative heights. Songs like “Synchronicity I,” “Synchronicity II” and “O My God” are immeasurably improved by Copeland’s busy yet tasteful drumming and Summers’ washes of jazzy treated guitar.

"I think what made The Police were the arrangements,” said Summers. “There was a three-way effort to come up with that sound, it wasn't just Sting. It was born of the chemistry between the three of us.”

The album’s second side is among the most commercially potent of the past three decades, with the Top 10 hits “Every Breath You Take” (which sat at No. 1 on the Billboard charts for a then-record eight weeks), “King of Pain” and “Wrapped Around Your Finger.”

But the more interesting and enduring of the two sides, by a long shot, is side one. Perhaps it is the ubiquity of those three monster hits on side two – or the more commercial nature that led them to be hits – but save for “Tea in the Sahara” and the cassette and CD bonus track “Murder by Numbers” – a song that provided needed comic relief from a band that never needed to be reminded to lighten up before now – it simply doesn’t hold up as well as the more eclectic, daring first side.

Most interestingly, what the album lacked was the thing that first gained the band notice – reggae, or in the coinage of manager Miles Copeland, Regatta de Blanc. Curiously, this seems to have been a calculated move to garner more mainstream airplay. "We took off the rough edges. Got rid of all the reggae stuff that Middle America couldn't handle,” Copeland said. While their white man’s take on reggae clearly helped drive the band’s early success, by Synchronicity, things were being taken far too seriously to allow such fun-time sounds to seep in.

Hearing the band in person on its reunion tour, and on subsequent recordings of those shows, I was amazed at how well these songs have weathered. Shorn of the studio wizardry and gloss that was endemic of the 1980s, they are muscular workouts by a surprisingly supple power trio. It reinvigorated my interest in the band and its music.

Before looking back, I held fast to the belief that the band had been as much a critical success as a commercial one. I was surprised then to find that while the band did garner good reviews, its stature among critics was closer to that of Coldplay than Radiohead, admired, but not necessarily loved. Plenty of derision was heaped upon the band for its slick sound, its pretentious singer, and its often comically earnest lyrical ambitions. “I prefer my musical watersheds juicier than this latest installment in their snazzy pop saga, and my rock middlebrows zanier, or at least nicer,” Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote of Synchronicity at the time.

The Police, in hindsight, seem like a transition of sorts for me. Had I encountered the band now as a jaded thirtysomething, I would likely be unmoved, scoffing at this boy band-turned-multinational corporation. But I discovered it as a 13-year-old fanatic-in-waiting looking for the right band to love. The Police was that band. While listening to Top 40 radio at the time, heavily influenced by what I saw on TV – songs from Duran Duran, Men at Work, ZZ Top and Big County in endless rotation – I was just starting to discover the music of bands that would mean much more to me over the long run, like U2 and Talking Heads. Meanwhile, bands that eventually changed my listening habits forever like the Minutemen, the Replacements and R.E.M., were making some of their most vital music, but they had no chance of denting my suburban Top 40 bubble as long as “Karma Chameleon” was piped into the mall sound system on a seemingly continuous loop. The Police somehow rose to the top of this pile – both in the culture at large and on my home hi-fi – as superstars who were on the radio for a solid year and as talented musicians and artists who continued to hold my interest over the next two decades in various incarnations as my horizons expanded exponentially.

“Somehow this thing thrown together works,” Sting said in the “Certifiable” DVD. “I don’t quite know why.” With my book about Synchronicity, I plan to get closer to the answer.

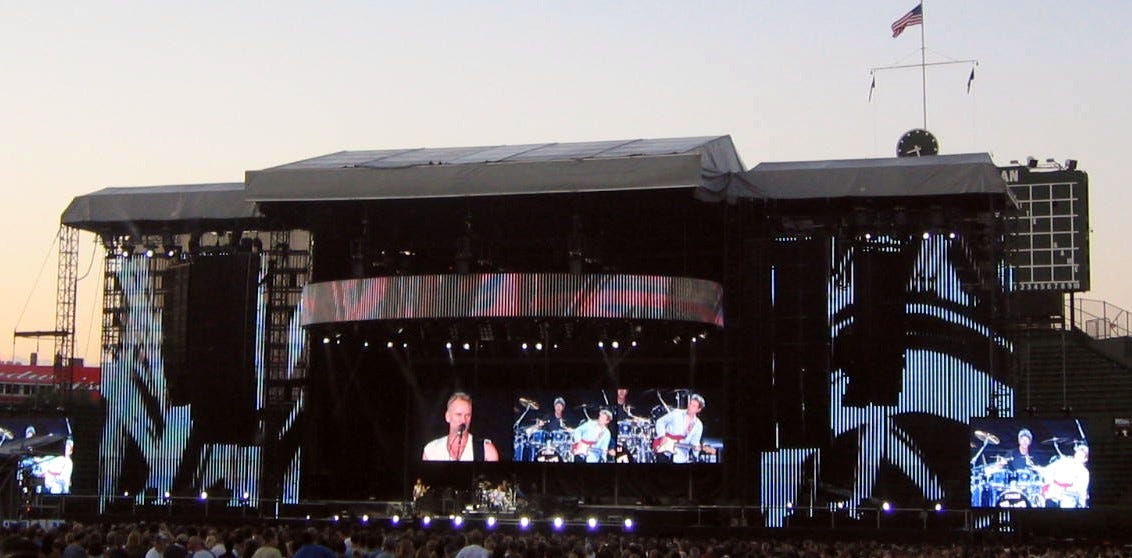

The Police rock Wrigley

from my Things I'd Rather Be Doing blog, July 6, 2007

As he probably has at every stop on the Police's reunion tour this summer, Sting tweaked the line "welcome to this one-man show" in the lyrics of "So Lonely," replacing "one-man" with "Andy Summers," then taking another spin through the verse to call it the "Stewart Copeland show." Whether it's a response to the well-worn fact that the three bandmates really don't like each other or simply a well-scripted cue for solo shots of the guitarist and drummer on the video screens above the stage, it's a cute if not terribly heartfelt shout out. The most interesting line of the song, however, is one that didn't change: "I always play the starring role." The difference between this being a Sting solo show or a Police concert is obviously the presence of Copeland and Summers, but without Sting, there would be no Police show, and that was clear every moment of Thursday's sold-out concert at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

As such, the show soared or sank depending on the frontman. Sting seemed engaged and on top of his game for most of the set, so the show was largely successful. The few times when he let things slip -- either because of key changes to songs that better fit his diminished range or because of a lack of interest -- it was obvious that Sting is the engine that drives the Police. The show started slowly, something attributable as much to the stadium's configuration as to the band's performance. With only the fattest of cats in front of the stage, and a several-yard gap between those seats and fans in the stands who were unwilling to part with $250 for the show, connecting took some time. As Sting's son, Joe Sumner, said from the stage during his band Fiction Plane's 30-minute opening act, "I wouldn't be able to hear you if you shouted for the rest of your lives." But once the sun went down and the light show took over, the Police clicked and the show took off.

That meant a slow build through "Message in a Bottle," "Synchronicity II" and "Walking on the Moon" (with an overlong audience participation segment) in the waning daylight. A segue from "Voices Inside My Head" into "When the World Is Running Down" sparked a bit of fire, but then Sting doused that with a bland, seemingly disinterested vocal on "Don't Stand So Close to Me." So, the first mega-hit of the night was a dud, and the subsequent run through several early tracks -- "Driven to Tears," "Truth Hits Everybody" and "The Bed's Too Big Without You" -- failed to engage all but the most diehard fans. The band played well, but the trio definitely needed the excitement of seeing a previously impossible occurrence on a gorgeous night at Wrigley to keep the crowd hooked.

Then, just as dusk turned to night, the band caught fire with "Every Little Thing She Does is Magic." Sting seemed to embrace the playful nature of the song, and the band's fiery performance overcame the lack of keyboards and multi-layered tracks that bolster the tune on Ghost in the Machine. The song seemed to energize band and audience alike and save for a couple of slowed tempos that made some songs drag, the rest of the concert was fantastic. While everything in the set was a hit, the final run that included "Wrapped Around Your Finger'' and the massive crowd sing-along "Roxanne" was everything one expected from this show.

By the time the band emerged for the first of two encores to tackle "King of Pain, "So Lonely" and Every Breath You Take" (which couples still swooned to despite Sting's assertion for the past 24 years that it's about a stalker), the literal gulf between band and audience had been bridged. Of course, why leave well enough alone? The trio returned for a second encore, a ragged run through "Next to You" that showed that while Copeland and Summers still have considerable chops, the manic tempos of their youth are largely beyond their grasp. Not that it mattered. This was no novelty act, but rather a band of pros who, while they may not like each other very much, certainly make great music together.

The question is, will that continue? Everything about this tour is steeped in nostalgia. The T-shirts feature images of the band from its earliest days, the color scheme of the tour mimics that of Synchronicity and the fast-cut video montage accompanying the set-closing "Next to You" (the first song on the band's debut disc) was a compendium of snapshots from throughout the band's history. The thing is, even 25 years later, no groups really sound like the Police. That was evident upon hearing Fiction Plane. That band's first disc was an edgy slab of modern, angular pop. In comparison, it's opening set on Thursday was composed of songs from its new second disc that sounded like those of a band trying to mimic the Police -- not an unwise move for a band with a vocalist who looks and sounds like the guy fronting the band that drew 40,000 people to the stadium -- and it sounded strange for the fact that no one else has tried to do it before. The tour is proving that people love this sound and the last three decades have proved that no one else seems capable of pulling it off (Sting on his own included), so who knows what the future holds? For now, it is enough to have finally seen the band, had a great experience and been left wanting more.

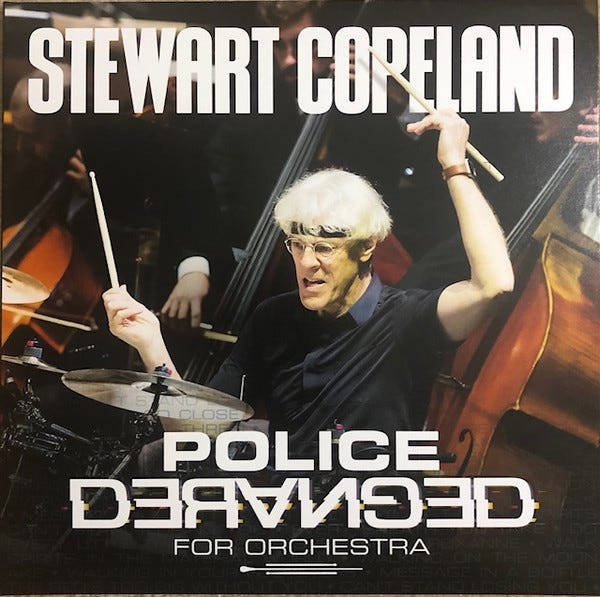

Stewart Copeland - Police Deranged for Orchestra

I've always loved Stewart Copeland, though I must admit at least some of that affection comes as it relates to the way he drives and irritates Sting. Listen to Sting's solo versions of the best Police songs, and you'll hear how pedestrian drumming leaves them lacking. And the further Sting gets from the Police, the blander and more boring his music becomes. Copeland was -- please forgive the tortured metaphor -- the grain of sand in Sting's oyster shell, the constant irritant driving the songwriter to create pearls that he simply can't match when surrounded by yes men.

At the same time, despite the charm of Copeland's early songwriting successes -- he penned many highlights on the band's first two albums, and his solo turn as Klark Kent is worth a spin -- or later instrumental work, he is at his best when propelling Sting's songs. I say that now with a caveat, for Copeland's latest project finds him doing just that, and failing in fairly spectacular fashion.

The Police Deranged for Orchestra, an album featuring the same “derangements” that Copeland has taken on tour the past few years, was released last week. The project's genesis is found in the music Copeland assembled for the documentary made from his Super 8 footage documenting the Police's early tours, “Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out.” He remixed the band's hits -- sometimes rather dramatically -- to create something new and at times revelatory. Sting didn't like the result and a planned release was shelved (though it can all be found quite easily on YouTube). He continued toying with the idea, and eventually created these orchestral "derangements."

“Delving into the multi-tracks of our original recordings and live performances revealed lost guitar solos, bass lines, and vocal improvisations that were just too cool to leave in obscurity," he said. "This discovery is what brings us to this performance: Sting’s songs, Andy’s inventions, and my impunity; all on the page for a wild ride with orchestra and unique musicians from around the world to adapt some of the most loved The Police hits for old and new audiences alike."

But this illogical extension, unlike that earlier project, reveals little new about the songs. I couldn't listen to it all in one sitting -- the human face isn't meant to cringe for that long -- but over the course of a few sessions I made it through and was left with only an overwhelming desire to hear the originals. I can imagine Sting hating this, too, but I'm sure he'll tolerate it because a) he probably makes more in songwriting royalties from each sale than Copeland does from mechanicals; b) it reminds people that no matter how integral Andy and Stew were to the sound of the band, he was the irreplaceable piece; and c) it will make people seek out his earlier symphonic take on the Police catalog.

Compare! Contrast!

Copeland is more adventurous, the arrangements more dynamic and livelier. That makes things more interesting, I suppose, but this setting doesn't fit the songs and they suffer for it. Though the relative sophistication of Sting's songs fades with each passing decade as younger musicians unhindered by the conventions of the '80s eclipse his efforts, there is still a feeling that can’t be replicated simply by placing the melodies and textures in different contexts. The supper club lounge feel of much of this does no favors to the songs. The obvious, tasteful arrangements found on Sting’s Symphonicities album aren’t much better, proving that not everything is improved by the presence of strings.

A few songs are tolerable – “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic” and “Murder By Numbers” aren’t bad – but nothing here would ever push aside the originals and demand to be played. I would much rather hear Copeland, who has done some inventive work away from the Police like The Rhythmatist and The Equalizer and Other Cliff Hangers, explore his own creativity rather than continue to mine that of his former band.

If you made it this far, drop in the comments and let me know if you still listen to The Police, what you think of Copeland’s “Derangements,” or anything else related to the band.